The Key to Elephants’ Future? Room to Roam.

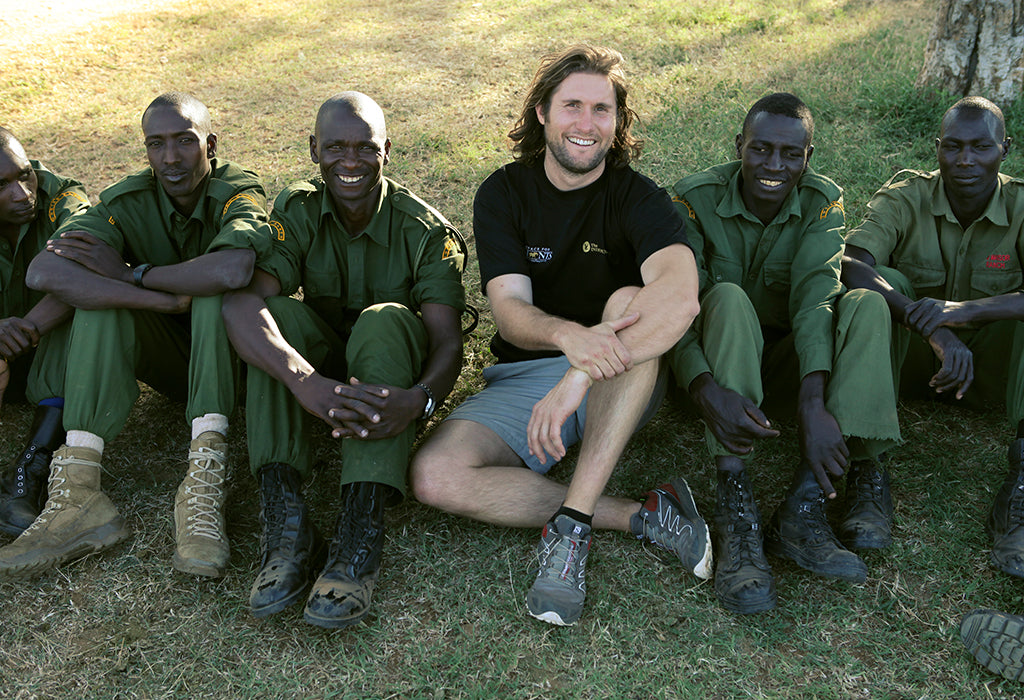

Dr. Max Graham, the CEO of Space for Giants—our Lip Veil and Luminescent Eye Shade philanthropy partner—has crafted a strategy for saving elephants while also protecting the people who live near them.

If you could conjure someone from central casting to lead the fight to protect Africa’s elephants, it would be Dr. Max Graham. Tall and commanding, equally comfortable in a tuxedo while dining with supporter and HRH Prince William as in a T-shirt and safari khakis, Graham inspires confidence with a sharp intelligence and a dogged pursuit of his goals. He has studied elephants since getting his PhD from Cambridge in 2007, where he researched why certain elephants break into farmers’ fields to feed on their harvests. This is a major issue called “crop raiding”—farmers retaliate and they or the elephants can get seriously injured as a result—and his work virtually eliminated the problem in certain parts of Kenya. Graham now dwells full-time in Nanyuki, Kenya, with his wife, Dr. Lauren Evans, and their two children. “It’s an incredible place to live,” he says, “and there are constant reminders of the work that is yet to be done to protect the wildlife that is all around us.” He stopped by Chantecaille’s SoHo office last spring to chat about the latest efforts by Space For Giants, and our partnership.

When did you have the idea for Space for Giants—what was the aha moment?

Space for Giants was founded in 2011, in response to poachers killing several elephants that I was studying. Right after that, there was an opportunity in North Central Kenya to acquire an important piece of land that was a critical corridor for elephants—so we worked with local and international partners to step up and make this transition happen. The journey has been going on ever since that moment. While addressing human-elephant conflict continues to be critical, the core of our work is focused on protecting the space that these animals need to survive. You might say it’s just as much about the Space as the Giants.

Founder Dr. Max Graham and wildlife rangers from Sosian Game Ranch in Laikipia. Photo courtesy of Space for Giants.

Can you explain what you mean by “elephant corridor?”

Elephant corridors are areas of land that allow elephants to move from one safe area of habitat to another. By defining these “corridors” that allow them to travel along their historic migration routes, we are protecting both the wildlife and the neighboring communities from an elephant that might “go rogue” and raid a farm or cross a busy road. If elephants have the freedom and security to move across the whole landscape, then they have a future forever.

What are the biggest threats to elephants in Africa?

Without a doubt, the biggest threat to elephants in the long term is the loss of their habitat and the resulting human-elephant conflict. That’s really what’s going to cause the disappearance of elephants forever. In the short term, however, we are facing a huge challenge with the illegal wildlife trade, especially around ivory, which has led to astronomical numbers of elephants being killed in recent years. For example, we know that 25% of the elephants alive in 2007 have since been killed for ivory. Those numbers are simply unsustainable. Thanks to commitment from conservation groups and government the rates of poaching have dropped in recent years, but there is still a long way to go.

Photo courtesy of Space for Giants.

What are some of the main ways in which Space for Giants protects elephants?

We approach the conservation of elephants and wildlife holistically, and from the point of view of local people. If elephants incur costs to local people, they’re a pest causing a subsistence crisis for small-scale farmers. So that cost has got to be managed and ideally reversed. One thing we do is make sure elephants don’t raid farms by putting in place “smart” or electrified fences that separate migrating elephants from the neighboring human communities. We also provide frontline protection to elephants, and that includes everything along the criminal trial process, from training rangers, to supporting prosecutors with the skills to secure higher conviction rates for poachers. The idea of that is to create a real deterrent. And most importantly, we are working now to encourage economic investment to build economies that benefit from elephants, like sustainable tourism. This type of investment makes elephant habitat valuable to both local people and national governments, ensuring elephants have a place to be safe into the future.

How do you do that? How do you convey its value to people and governments?

We turn wild habitat into hubs of employment, of revenue generation, of tax generation, of healthcare and education. We do that at the moment by supporting enterprises like tourism, but also conservation-compatible livestock enterprises that bring revenue into these really important natural landscapes. The trick is to scale it up to a level that is truly meaningful, so there are enough wild places that are secure to maintain Africa’s elephant population forever.

"Last year we had zero incidents of poaching."

Photo courtesy of The Film Farmers/Space for Giants.

How would you measure the success you’ve had so far?

In North Central Kenya, where Space for Giants is headquartered, we had a major poaching crisis in 2011, creating over 100 orphaned elephant calves. To address this crisis, we supported the training of 177 rangers, created special operations teams, and built capacity in the criminal trial process to result in more effective convictions. Last year we had zero incidents of poaching.

Along the landscapes where we’ve put electrified fences in place, such as Uganda and Botswana, we’ve seen human-wildlife conflict decrease from levels where tens of thousands of farmers were literally having a subsistence crisis as a consequence of elephant damage, to incidents in very limited numbers, about 4 or 5 a year. In Uganda, a proposition for the tourism industry has brought in investors who could bring at least 65 million dollars of new tourism investment ventures.

Another key metric of conservation success in the wildlife trade is conviction rates. In Kenya in 2014, rates of conviction were 26 percent for the wildlife trade, and last year it was just under 90 percent.

What are some specific initiatives that the Chantecaille partnership—which started last year with the launch of Lip Veil—has supported, and what are the outcomes?

The Chantecaille partnership has enabled us to scale up our damage prevention toolkit program for farmers out of Kenya and into parts of Gabon and more recently into Uganda and Botswana. Secondly, we’ve been able to scale up the protection of elephants from the illegal wildlife trade in the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area. It’s 500,000 square kilometers—a massive challenge—and the Chantecaille partnership has allowed us to bring anti-poaching support to that landscape to create a deterrent to those who would kill elephants for ivory.

You get up close to elephants from time to time. Have you had a close brush with any?

I’ve been nearly killed by elephants so many times I’ve lost count. But I’m fortunate enough that they haven’t caught me yet. When I was 22, I was walking with a friend in some very thick bush. We looked up to my right and the bushes started shaking. I didn’t know what this thing was, whether it was a buffalo or a lion, and then the tops of these ears showed up. There was nothing I could do at that point. I asked the ranger I was with if he could shoot in the air, but he froze, so the only thing to do was run. I turned and I ran and the elephant caught right up to me. I made it to the bushes and I was literally crawling—it was so close I could feel the breath of this elephant on the back of my neck. I thought I was done for! Just then I dropped about 13 feet down a sort of a cliff or ledge and could see elephant’s trunk just above me. After searching a minute, she picked it up, put it in the air and walked away.

The very next day we found a dead, recently poached elephant at the bottom of that same cliff. So, what had happened is my elephant had been traumatized from a poacher killing a member of its family and seeing me walking through the bush with my friend who was armed, we were seen as a threat, so he attacked. Each individual elephant has a story; they marry these memories that enable them to navigate risk in space in time, and sometimes those memories contain negative experiences of people. So that’s why if you approach an elephant and you don’t know it, you need to approach with real respect and caution.

For someone who is half a world away but inspired to get involved with wildlife conservation, what’s the best thing we can do to help?

I think increasingly the best way to get involved in conservation is to do one of three things: Make sensible decisions about what you buy. There’s an opportunity in your daily consumption patterns to turn those patterns into units of conservation. So a product like Chantecaille genuinely, from my perspective—if you can buy something that contributes to elephant conservation, that’s real a win-win. The second thing is to visit countries where there are elephants. Go and visit their national parks, because the dollars you’re spending end up in the pockets of the people, going into infrastructure, schools, hospitals, and that all means that elephants become more powerful, which means they have a better chance of survival. And the final thing is look carefully but invest in charitable work that’s supporting elephants. Invest in it with your money, invest in it with your time and your expertise, but make sure that you’re considering the way you spend your life has an impact on the future of the species and the natural ecosystems they live in.